Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

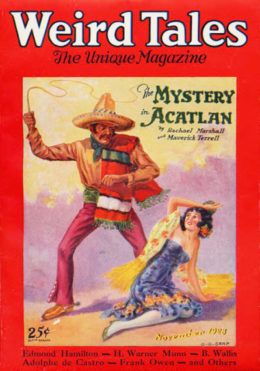

This week, we’re reading H. P. Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro’s “The Last Test,” a revision of de Castro’s original “A Sacrifice to Science,” first published in In the Confessional and the Following in 1893; the revised version first appeared in the November 1928 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“Humanity! What the deuce is humanity? Science! Dolts! Just individuals over and over again!”

Summary

Few know the inside story of the Clarendon affair, which culminated in the death of genius bacteriologist Alfred Clarendon. His longtime friend and supporter, Governor James Dalton, and his sister Georgina, now Mrs. Dalton, know the truth, but they never speak of it.

Clarendon traveled the world seeking an antitoxin to cure the many fevers plaguing mankind. Monomaniacal and negligent of worldly affairs, he relied on Georgina to manage his finances and household. That their father had refused Georgina’s hand to Dalton struck him as lucky, for Georgina’s memories of her first love kept her single. Who else, after all, would have tolerated such eccentricities as his chosen servants? From Tibet, where he discovered the germ of black fever, he brought home eight skeleton-lean men, black-robed and silent. From Africa, where he worked on intermittent fevers among the Saharan Tuaregs (rumored descendants of the primal race of Atlantis), he acquired a factotum named Surama. Though intelligent and erudite, Surama’s bald pate and emaciated features gave him the appearance of a death’s-head.

In 189-, the Clarendons move to San Francisco and reunite with Dalton. Frequent calls lead to renewed tenderness between the lovers and a political appointment for Clarendon as medical director of the San Quentin State Penitentiary. There he hopes to find a broader scope for research. His hope is soon fulfilled in an outbreak of the very black fever he encountered in Asia.

Fever spreads among the prisoners, though Clarendon maintains it isn’t contagious. This doesn’t convince the public of San Francisco, driven to panic by a sensation-hungry press. Fellow doctors accuse Clarendon of undertreating patients to study the course of their disease. He ignores them while Surama chuckles. One reporter sneaks onto Clarendon’s mansion grounds, to find caged experimental animals and a private clinic with barred windows. Surama expels the intruder, who takes revenge by inventing scurrilous stories about the famed doctor. Dalton does his best to counter the bad press and comfort Georgina.

The two renew their engagement. Clarendon, however, refuses his blessing—how could his old friend expect Georgina to abandon her vital service to science? Georgina persuades Dalton to be patient—her brother will come around.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

The anti-Clarendon faction, meanwhile, gets him dismissed from San Quentin. Clarendon lapses into rage, then depression, and languishes at home under Georgina’s anxious care. He neglects even his private clinic; Surama retreats to his basement quarters from which issue “muffled rhythms of blasphemous strangeness and uncomfortably ritualistic suggestion.”

Following a particularly intense “ritual,” Clarendon returns to enthusiastic work. Georgina overhears him complaining to Surama that they’ve run out of experimental animals, and besides it’s really human subjects he needs. Surama chastises him for childish impatience, but suggests they use “the older material.” Soon after, Georgina’s horrified to see Surama drag one of the Tibetans into the barred clinic. Clarendon rants about how no individual matters in the quest for knowledge.

But even Surama seems to hesitate when Clarendon has Georgina’s sick dog carried into the clinic. Georgina telegraphs Dalton, begging him to come. The remaining Tibetans vanish. Desperate, Georgina approaches the clinic and hears Clarendon curse his factotum for preaching moderation at this late date—Surama with his “devilish Atlantean secrets” and his “damned spaces between the stars and […] crawling chaos Nyarlathotep!”

Clarendon finds Georgina unconscious in the library. He revives her in a “brotherly panic” which turns to calculating appraisal. He wonders aloud if she’d be willing to sacrifice herself to the cause of medicine in order to bring about the completion of his work. Well, they’re both worn out. They could use a dose of morphia—he’ll go and prepare a syringe.

Dalton arrives. Georgina tells all. Alone, Dalton waits for Clarendon. When the doctor arrives, he distracts him with an article by one Dr. Miller, who claims to have found a serum to defeat black fever. Clarendon begins incredulous, finishes with a wild scream of despair. He injects himself with the “morphia” prepared for Georgina. A confession follows. The Tuareg priests led him to a sealed place where he revived something ancient and evil: Surama. And Surama taught him to worship unholy gods. Mapped out a goal too terrible to tell, for the sake of Dalton’s sanity and the world’s! What Miller has cured isn’t the true black fever, a gift from Surama from beyond earth. When Clarendon injected subjects with it, it was never for science, it was only to kill and revel in killing, such was the corruption to which Clarendon has yielded!

Now he himself will be the last test subject. Dalton can’t save him, but he can destroy the private clinic and everything in it. And he must destroy Surama, who can only be put down with fire.

As it turns out, the deathly ill Clarendon creeps out to burn the clinic off-screen. Later searchers find Clarendon’s blackened skeleton—and another, neither quite ape nor saurian though its skull looks human. Indeed, it looks like Surama’s.

What’s Cyclopean: The flames of the burning clinic, which resemble some creature of nightmare.

The Degenerate Dutch: Clarendon’s Tibetan servants are “grotesque” in aspect, though they ultimately turn out to be his victims rather than responsible for any of the horrors. On the other hand, the “mysterious Saharan Tuaregs” in “secret and aeon-weighted Africa” will totally share the secrets of ancient Atlantis with you, and send you off to call up eldritch horrors. The “all brown people worship the elder gods” theme, while not as blatant here as in some other stories, is definitely playing in the background.

Mythos Making: In addition to all the elder gods with whom Clarendon gets involved, there are references to Irem and Alhazred.

Libronomicon: Dalton is disturbed by Clarendon’s bookshelf, which has “too many volumes on doubtful borderland themes; dark speculations and forbidden rituals of the Middle Ages, and strange exotic mysteries in alien alphabets both known and unknown.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Lots of madness this week, ranging from mass hysteria in San Francisco over a few fever cases in a prison to Clarendon’s ranting breakdown. In our read of “The Electric Executioner,” we commented that de Castro is more prone than Lovecraft to giving us mentally ill villains rather than victims, and that pattern holds here.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Sometimes it’s fun to speculate about whether a couple of people with similar ideas might have crossed paths, or whether they just drew on some common thread of human propensity. Did Hagiwara Sakutaro get a peek at Ulthar? How much did Jean Ray know about Cthulhu? Such connections make for pleasant speculation and diverting flights of fancy, as we imagine trysts in extradimensional cat cafes.

Sometimes, the striking-yet-improbable connections aren’t fun at all.

It is, in fact, extremely unlikely that some SOB in the U.S. Public Health Service read a bloated Weird Tales novella in 1928, and thought the tragic villain had a great idea. But I just can’t get out of my head the fact that, four years after the revised story came out in the pulps, the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study began. All too familiar, this plot: Research is begun with vague intentions of improving medicine, but quickly transmutes to a decades-long travesty of observing the painful progression of untreated patients, as they suffer debilitating symptoms that could have been prevented. Lovecraft and de Castro’s pseudo-doctor even follows the same expedient to avoid notice: Shielded by his own privilege and reputation, he knows no one will track maltreatment of a few Asian servants far from home, or prisoners. Or African American men in the deep South. Our authors are disturbingly on-target in their understanding of how unethical experiments pass below the radar—and particularly how they did so in an era where regulations for human subjects protection would’ve been wild SFnal speculation.

So what’s more disturbing: the unlikely chance that a plot point from Weird Tales wedged itself into Thomas Parran Jr.’s brain and set him on an evil path, or the near-certainty that de Castro and Parran just drew on some common thread of human propensity?

This line of consideration has diverted and distressed me far more than the story itself, which I mostly found tedious. I spent half the time cataloging the degree to which each of the characters made themselves unpleasant: Dalton with his stalwart failure to talk to his girlfriend on any useful time frame, Clarendon with his pompous insistence on scholarly monasticism, Georgina with her refusal to cut the story short by LEAVING THE DAMN HOUSE, JUST GET OUT OF THERE GIRL. I realize 1928 is a little early to be genre-savvy, and yet there was already a rich tradition of horror movies and Gothic novels in which LEAVING THE DAMN HOUSE is a really good idea. It might even have helped people beyond Georgina herself, because without her running the household and making the budget go, Clarendon would likely have fallen afoul of failure to pay property taxes or something, and gotten his clinic investigated.

I spent the other half of my reading considering how badly I wished that Hazel Heald, and not de Castro, was Lovecraft’s collaborator here. This is a hopeless counterfactual since “The Last Test” started as an unadorned de Castro story. But if Heald had been there, Georgina would have done something other than faint and we could have had a nice tight novelette instead of waiting around for almost 20,000 words (I counted) before she admits to herself that just maybe not all is right in her brother’s head.

The third half of my reactions (the non-Euclidean half) is devoted to considering how much more could have been done with the concept of a pain-eating Atlantean lizard-person. I wanted fewer sordid hints about terrible tortures, and more implausibly communicative ancient bas-reliefs.

Anne’s Commentary

Adolphe de Castro first published “The Last Test” and his other Lovecraft revision “The Electric Executioner” in 1893, in a collection called In the Confessional and the Following. That version of “The Last Test” was titled “A Sacrifice to Science,” which makes me wonder about its original focus. It couldn’t have been Alfred Clarendon’s seduction by a revivified priest of Nyarlathotep, since the creator of the Cthulhu Mythos was only three at the time of its publication, “Nyarlathotep” still but a handful of nonsense syllables in search of a terrible Outer God to own them. “Sacrifice to Science” suggests that the privations and perils of Georgina Clarendon might have taken center stage, since she would have been Alfred’s ultimate offering to the Goddess Knowledge save for the intervention of square-jawed James Dalton.

Heroes always have square jaws, have you noticed? There must be a link between the genes governing mandible shape and valor-slash-chivalry. Whereas intellectual villains such as mad scientists usually have pointed chins made more pointy by tapered goatees, as is the case with Alfred Clarendon. Alfred also wears pince-nez, close relative to the monocle, so there can be no doubt about his role in the melodrama. The myopia of the villain is a physical manifestation of his spiritual blindness and, often, his overweening ambitions. That he can’t just wear thick-lensed horn rimmed glasses is what separates him from benevolent geniuses.

Whereas Georgina’s hereditary weakness is selfless devotion and a pathologically enormous capacity for long-suffering. No problem—it’s a common and useful trait for heroines of the saintly variety. Otherwise why would they stick around the villain long enough to face sufficient peril? Plus selfless devotion is highly attractive to square-jawed heroes, to whom it must inevitably be transferred.

My point being: This week’s story is a mess. On a melodramatic skeleton is layered so much Mythosian paraphernalia that the bone structure’s overwhelmed under the meat. It’s not that the added flesh isn’t good, doesn’t have the potential to make a tasty fictive dish. Private libraries full of blasphemous tomes may make one wonder how rare said tomes can be, given their ubiquity, but we can overlook that if the books are put to good use. It’s always nice to read the names Yog-Sothoth and Nyarlathotep and Shub-niggurath, but disappointing if those are merely names dropped as superficial seasoning. Surama and the eight silent Tibetans could fascinate. Surama especially, survivor of an Atlantis whose inhabitants weren’t exactly human and whose wisdom and works a merciful heaven would leave sunk deep. His bones have saurian aspects—could he be related to the Serpent-men of the Nameless City? He’s in league with the stars and all the forces of nature! He has a terrible goal that Alfred can’t hint at, for the sanity of the world! He teaches the young genius paleogean rites that addict him to murderous pleasures and swamp all wholesome scientific zeal! Sure, Surama does chuckle a lot, but his chuckles are blood-curdling and bone-chilling, so that’s cool.

Not so cool for Surama to suddenly turn more squeamish than his pupil and feel bad about Georgina’s pet dog. Or to scold Alfred with lingo like “You’re no fun anymore” or “I thought you had the stuff in you, but you haven’t” or “Shut up, you fool!” Oh, Surama, it so breaks the mood. In the ranks of reconstituted evil wizards, you’re not in the Joseph Curwen league anymore.

And I would like some clue about Surama’s terrible world-maddening goal. My sanity can take it, Alfred, I promise.

And, unfortunately, all the coolest stuff takes place off-stage, in long stretches of expository dialogue. I’m wishing I could’ve actually traveled with Alfred, met the man in China who knew Yog-Sothoth or the old chap in Yemen who came back alive from the City of Pillars and the underground shrines of Nug and Yeb. Tantalizing allusions like these are standard Lovecraft technique, sure. But I don’t know—if Howard weren’t constrained by the original structure of “Last Test,” might he not have taken us to the secret place where Surama lay dormant for millennia? Might he not at least have taken us into the clinic to witness the final confrontation?

Summing it up, I’m afraid that revising this non-Mythosian tale to include the Mythos didn’t work for me. Neither Georgina nor Dalton do much to earn their happy ending and justify the romantic subplot. The San Quentin subplot is another promising avenue that peters out.

Yeah. Sorry, Adolphe and Howard. For me, “A Sacrifice to Science” and “The Last Test” were not a match made in heaven, or a thoroughly enjoyable hell.

Next week, Karl Edward Wagner’s “I’ve Come to Talk with You Again” offers a cautionary tale for Lovecraftian writers who can be tempted to make bad deals. You can find it in Lovecraft’s Monsters. (And this week, you can find Ruthanna at the Charm City Spec reading in Baltimore on Wednesday night, and then in Boston for Arisia—hope to see some of you there!)

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.